All The Essentials On Using Reference Tracks in Music Production (…And A Couple Less Talked About Tricks)

Reference tracks sit at the center of how I finish music consistently, especially when I want a track to translate outside my room without second-guessing every decision I make late in the process. I rely on them as a calibration tool, a reality check, and a way to move forward with confidence instead of hesitation, and if using reference tracks is good enough for Armin Van Buuren, it should be good enough for artists like you and me.

When I talk about reference tracks, I mean finished records that already work in the environments I care about, whether that is clubs, headphones, cars, laptops, or streaming platforms. These tracks give me a fixed point of comparison when my ears start drifting after hours of looping the same section, which matters because isolation changes perception in ways most producers underestimate.

At A Glance

After enough repetition, balances that are off start to feel normal, energy differences flatten out, and decisions slow down because nothing feels clearly right or wrong anymore. Reference tracks pull you out of that bubble and reset your frame of hearing.

What follows is how I actually use reference tracks during production, from sound selection and gain staging to frequency balance and arrangement layout, using methods that remain practical and repeatable across sessions rather than theoretical. While using reference tracks is certainly not the most difficult thing a new producer can start doing, it’s also something you should first know the basics to start implementing, in which case you should check out Izotope’s essential guide on mixing music, which can help get you up to speed fast.

Using Reference Tracks for Style and Sound Selection

Before I worry about mixing or automation on your plugins, I use reference tracks to lock in sound direction, because this step prevents me from designing sounds that later fight the track’s identity. I listen with specific questions in mind, asking how short or long the drum hits are, how dense the percussion layer feels, how much movement exists inside sustained elements, and how controlled the reverb tails sound across sections.

This is where tools built for fast sound exploration help a lot. Bloom Mura Masa fits naturally into this stage because it allows me to sketch rhythm driven ideas quickly while staying focused on musical function rather than technical depth in your tracks. I use it to explore parts that occupy similar roles to what I hear in the reference, whether that means percussive phrases that fill midrange motion, tonal stabs that support groove without crowding the lead, or textural movement that stays contained and repeatable.

I adjust macros until the sound behaves the way the reference behaves, then I stop. That stopping point matters because the goal here is alignment of function rather than refinement for its own sake. Once the arrangement feels stable, I can replace or refine sounds later if needed, but the foundation holds because it was guided early by reference listening.

Choosing the Right Reference Tracks Before You Touch a Fader

The first mistake I see producers make with reference tracks is choosing too many, or choosing tracks that do not actually answer the questions they are asking. More references do not lead to better clarity if each one pulls your ear in a different direction. I usually work with 2 or 3 reference tracks in total. One defines the stylistic lane I want to sit in, one helps me judge mix balance and overall energy, and a third can help with arrangement pacing if the structure of my track starts to feel uncertain.

Tempo range matters. Drum programming density matters. Overall arrangement thickness matters. If those foundations are misaligned, the comparison stops being useful and starts creating confusion instead of clarity. Before I even listen critically, I write short notes for each reference so I know exactly why it is there. I might note low end weight, lead placement, or how restrained the high end feels, and those notes guide what I listen for instead of letting my attention wander.

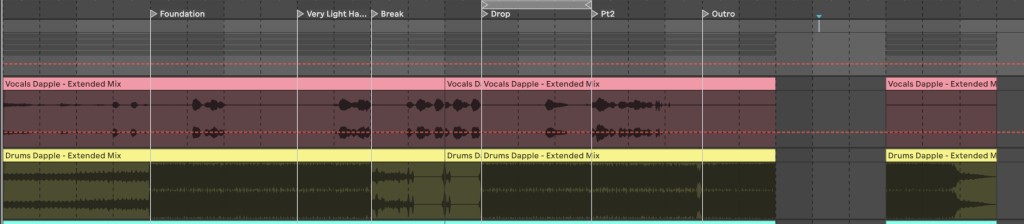

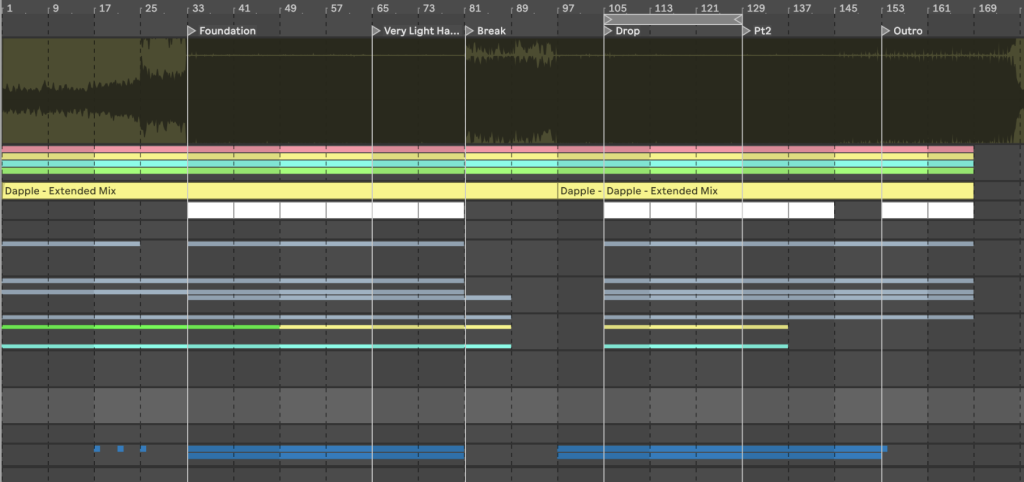

I also drop markers into the reference track itself, marking the intro, first groove, main section, breakdown, return, and outro. This lets me jump to equivalent moments and compare like with like, rather than drawing conclusions from unrelated sections. If a reference does not serve a clear purpose after this process, I remove it. Fewer references with clearer intent lead to faster decisions and far less second-guessing.

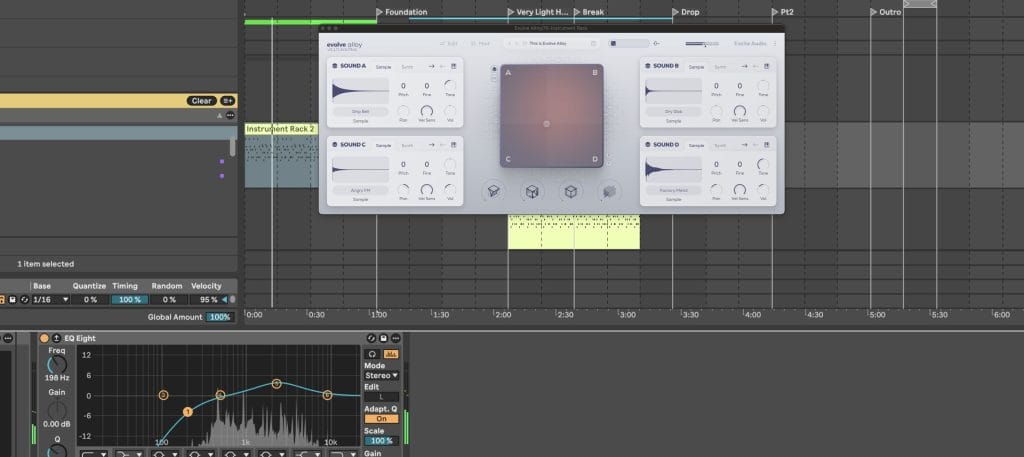

When referencing the track we’re using, I noticed that while many of the lead synth sounds are very synthetic, as if they’re from something like Diva or Spire, much of the percussive and transient-heavy melodic ear candies come from more acoustic or foley-based meldoic sources, which instantly makes me want to grab Evolve Alloy by Excite Audio as it makes replicating and synthesizing these excact types of sounds easier than ever and it’s one of my favorite tools for exactly this type of thing.

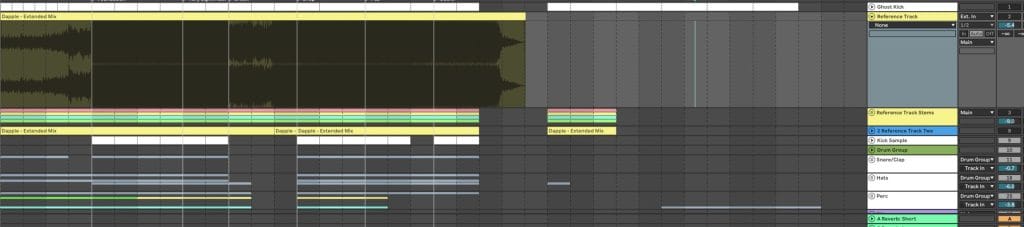

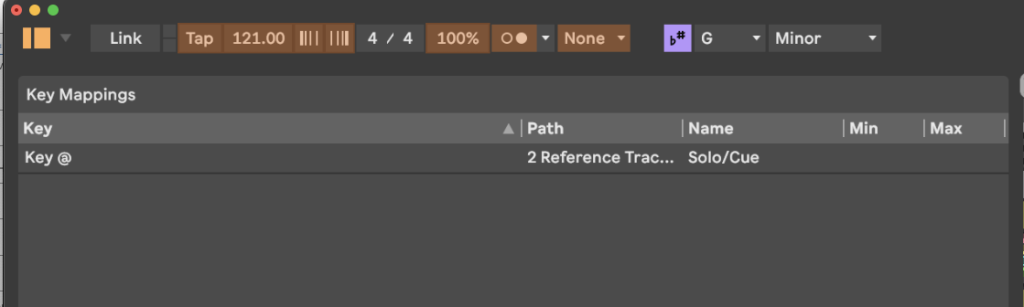

Setting Up Your Session So Reference Tracks Stay Honest

Reference tracks need a dedicated place in your session, and they need to stay isolated from processing that belongs to your mix. If this setup is wrong, every comparison you make becomes unreliable before you even start listening. I route reference tracks directly to the output, bypassing any bus processing or master processing that I am using on my own track, because I want to hear the reference as it exists in the real world, not filtered through my session chain.

I also make switching fast and effortless, whether that is a keyboard shortcut, a controller button, or a simple mute group. If switching feels clumsy, you will avoid doing it, and reference tracks only work when you check them often and briefly. I like to time align reference tracks to my project grid when possible because even if the tempo differs slightly, alignment helps the brain compare structure, density, and movement without fighting timing differences.

This setup lives in my default template. I never rebuild it from scratch, because reference tracks should feel like part of the room itself, always present, never disruptive, and never treated as an extra step.

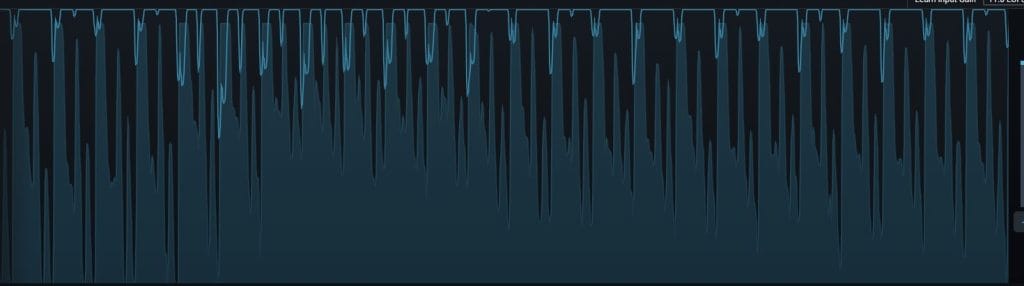

Level Matching First So Loudness Stops Lying to You

Every mix needs an anchor, and in dance-oriented production, that anchor is usually the kick. Without a fixed reference point, gain staging turns into constant recalibration. I set the kick level early and treat it as fixed while building everything else around it, which gives the mix a stable center and keeps level decisions consistent across sessions.

I use reference tracks to judge how forward the kick feels relative to the bass and the rest of the drums, listening closely to midrange articulation and the length of the low-end tail. Once the kick feels right, I bring in the bass and shape their relationship until low frequencies feel controlled and readable, and only after that relationship stabilizes do I build the rest of the track.

This method simplifies decision-making because instead of juggling everything at once, I solve one relationship at a time using the reference as a constant guide.

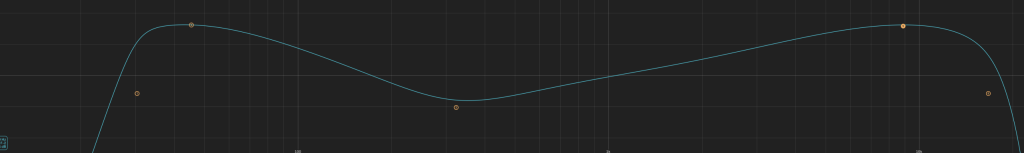

Loudness changes perception more than most people realize. A louder signal feels fuller, clearer, and more finished even when nothing else improves, and this single issue causes most reference track frustration. I always level-match before making judgments, which means trimming the reference track until switching back and forth feels equal in perceived loudness for the specific section I am comparing.

I work with short loops, usually eight to sixteen bars, and I match by ear first before confirming with metering if needed. The goal is perceived balance, not matching numbers perfectly. Once loudness bias is removed, real differences show up immediately, whether that is low end weight, midrange clarity, high frequency restraint, or arrangement density. Those differences guide meaningful decisions instead of sending you chasing ghosts.

Skipping this step guarantees confusion later. Spending one extra minute here saves hours of fixing problems that were never actually there.

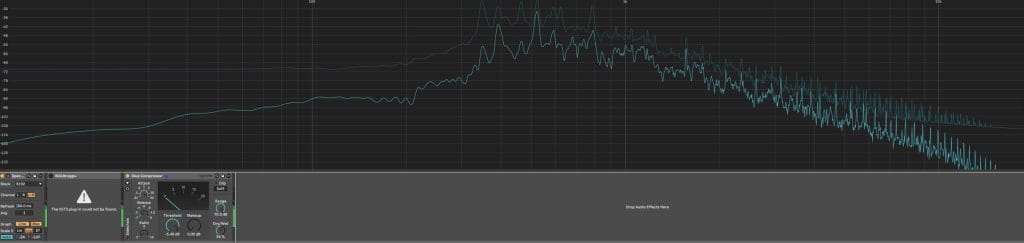

Checking Frequency Balance and Energy Across the Spectrum

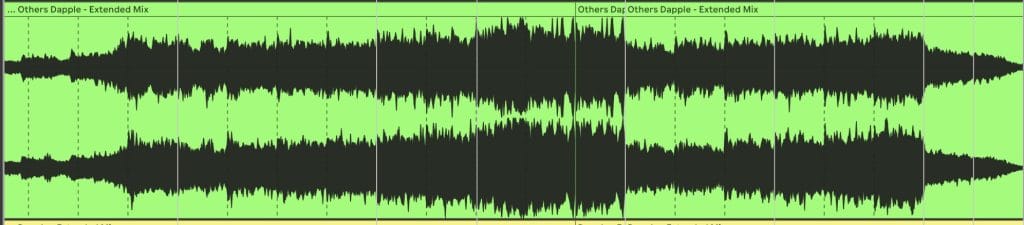

After sound selection, reference tracks help me verify frequency balance in a grounded and repeatable way, which keeps me from over-correcting based on fatigue or room bias. I break the spectrum into broad regions and listen for energy distribution instead of chasing narrow problem areas, paying attention to sub range weight, low range fullness, midrange clarity, upper presence, and high frequency restraint.

I loop equivalent sections and move band by band, asking one simple question for each region: does my track feel heavier, lighter, or comparable to the reference here. When something feels off, I make small adjustments, such as a subtle level move, a gentle filter shift, or a restrained EQ change, and then I listen again before stacking changes.

Visual tools help confirm what I hear, but they never replace listening, because arrangement differences always affect spectral shape. This approach keeps decisions calm and controlled and prevents the mix from slowly drifting away from the original intent.

Critical Listening Prompts That Keep You Objective

Reference tracks work best when listening stays focused, because without prompts, the ear wanders and conclusions become vague. I ask specific questions, such as how loud the lead sits compared to the drums, how wide the supporting elements feel, and how deep the space feels without sacrificing clarity. It’s how artists like OHMFIELD ensure his mixes stay clean and tight when he says:

“Get a solid list together of different reference tracks for each project you start as Metric AB really lets you obsess over every minute different in your mix. It’s one of those plugins that you could without but Metric AB just makes it so much easier. Since I started using it I know that my mixes have improved tenfold.”

I listen for how processing shapes movement across sections, how energy changes between parts, and how transitions feel without relying on effects to do all the work. I take short notes during this process, not essays, but simple reminders that guide the next round of adjustments.

These prompts turn listening into action instead of analysis loops that stall progress.

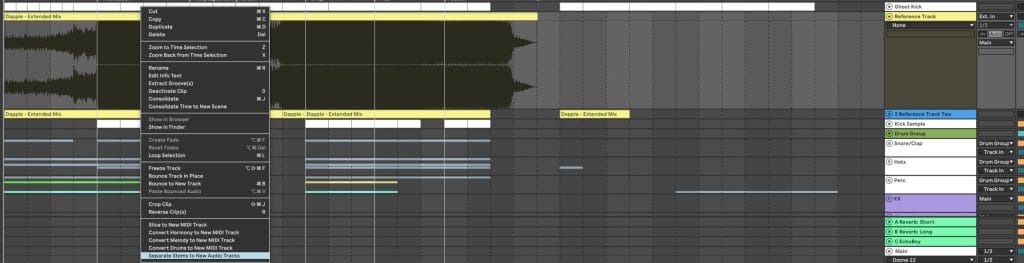

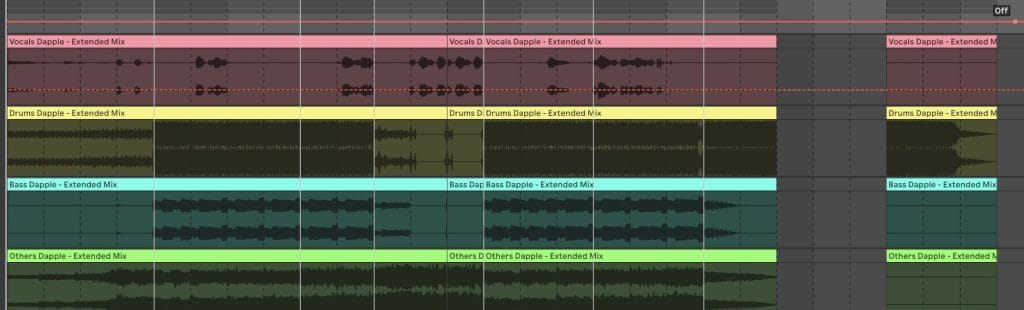

Using Reference Tracks to Shape Arrangement and Track Layout

Arrangement benefits from reference tracks as much as mixing using some of the most popular plugins from last year does, especially when attention span and pacing matter. I map section lengths and energy changes, count bars, mark where elements enter and leave, and note how long tension builds before release.

This gives me a structural frame to work within. I am not copying arrangements, but I am learning how long ideas hold attention and how to space transitions. I pay special attention to moments of reduction, such as breakdowns and sparse sections, because these often carry more impact than busy ones.

When my track starts feeling rushed or overstretched, I return to these maps and recalibrate with clarity instead of guesswork.

A 15 Minute Reference Pass You Can Run Anytime

When time feels tight, I run a short reference pass to regain clarity. I pick one section, level match, check kick and bass balance, scan broad frequency regions, confirm lead level and width, and glance at arrangement markers.

I write down three adjustments and make them immediately, which keeps progress moving forward without spiraling into endless revisions.

Closing Thoughts

Reference tracks keep me grounded. They anchor decisions, speed up workflow, and protect perspective when fatigue sets in.

Used correctly, they reduce uncertainty and make finishing tracks feel manageable instead of overwhelming. If you want to move faster and finish stronger, build reference listening into every session and treat it as part of the process rather than an extra step.

Frequently Asked Questions About Using Reference Tracks in Music Production

How do you properly use reference tracks?

I treat reference tracks as a calibration point rather than a target to chase.

The first step is always level matching so loudness does not influence perception, followed by comparing equivalent sections like drops or choruses rather than full songs. I focus on one aspect at a time, such as low-end balance, vocal placement, or overall density, instead of trying to evaluate everything simultaneously.

Short, frequent comparisons work better than long listening sessions because they preserve objectivity. I also return to the same reference tracks throughout the project so my decisions stay consistent from early production through final mix checks.

What is a reference track in music production?

A reference track is a finished recording used to guide decisions during production, mixing, or arrangement. I use reference tracks to understand how elements relate to each other in real releases rather than relying solely on memory or imagination.

These tracks provide context for balance, energy, and structure in ways raw sessions cannot. They also act as a reality check when fatigue sets in and perception shifts. A good reference track answers specific questions instead of serving as general inspiration.

Do professionals use reference tracks?

Yes, reference tracks are part of everyday workflow for experienced producers, mixers, and mastering engineers. I have yet to meet anyone working at a high level who relies entirely on instinct without external comparison. Reference tracks help maintain consistency across projects, especially when working in different rooms or on different systems.

They also reduce revision cycles because decisions are grounded in proven results. Using reference tracks signals discipline rather than uncertainty.

Does reference audio help with EQ decisions?

Reference audio helps guide EQ decisions by providing context for overall balance across frequency ranges. I listen for how much space different elements occupy rather than copying specific curves or settings. This approach helps identify areas where energy feels crowded or thin relative to the reference. Broad tonal balance becomes easier to judge when loudness has been matched. EQ moves become smaller and more intentional when guided this way.

What are common EQ mistakes to avoid?

One common mistake involves making large EQ changes without checking how they affect the mix as a whole. Another issue arises from focusing on soloed tracks rather than evaluating changes in context. Over-correcting perceived problems caused by monitoring conditions also leads to unstable results.

I also see people adjusting EQ before the gain balance has been established, which complicates decisions later. Reference tracks help keep EQ work grounded in musical outcomes rather than in visual feedback.

Should bass or treble be higher in a mix?

Balance between bass and treble depends on genre, arrangement, and playback environment rather than a fixed rule. I listen for how low frequencies support the groove while keeping midrange elements clear.

Treble provides definition and space, yet excess energy there can shift attention away from the core elements. Reference tracks clarify how these regions coexist in finished releases. The goal involves proportion and stability rather than emphasizing one range.

What EQ works best for footsteps?

For footsteps or similar transient sounds, I focus on shaping the midrange where articulation lives. Low frequencies can be reduced to prevent rumble, while upper mids help define texture and placement. The exact ranges depend on the source and context, so I adjust while listening against reference material from similar environments. Small, controlled moves preserve realism. Context always determines final settings.

Can too much treble damage speakers?

Excessive high-frequency energy can stress speakers over time, especially at elevated playback levels. I keep treble balanced by referencing commercial material played at similar volumes. Harshness often appears as fatigue before equipment issues arise, which serves as an early warning sign. Smooth high-frequency balance translates better across systems. Reference tracks help keep this region controlled without dulling clarity.

What are the perfect EQ settings?

Perfect EQ settings do not exist as fixed values because each sound and arrangement demands different treatment. I approach EQ as a response to context rather than a preset to apply.

Reference tracks help define the direction of balance without prescribing exact numbers. Decisions remain flexible throughout the process as the mix evolves. The most reliable results come from listening, adjusting, and confirming against trusted material.