Xenoangel simulate mythic archaeology on the back of a world beast in Supreme (Slow Thinking)

Multidisciplinary artists Marija Avramovic and Sam Twidale combine live simulation, hybrid poetry, 3D animation and reactive sound design to explore symbiosis and synchronicity in a world which is both ecosystem and organism.

Marija Avramovic and Sam Twidale describe themselves as “scavengers of virtual worlds.” Since 2017 they have been working collaboratively as Xenoangel, combining their multidisciplinary practises to create worlds animated with an intricate fantasy cosmology of interconnected systems, media, organisms and objects in order to further explore and develop a variety of research interests and influences. Whether taking on the existentialist thought of Jean-Paul Sartre in After Intelligence (2018), interpreting the magical realist cinema of Akira Kurosawa alongside animist and techno-animist beliefs with Sunshowers (2019), or coding political theorist Jane Bennet’s theory of ‘vibrant matter’ onto Arkady and Boris Strugatsky’s 1971 science fiction touchstone Roadside Picnic in The Zone (2019), Xenoangel build virtual ecosystems that are complex and expansive enough to encapsulate the broad scope of their thought. “It’s about making worlds which are autonomous and independent of us,” explains Avramovic. “It’s really about watching a universe from the perspective of the observer.” In their latest work, Supreme (2021), the artists utilise the object oriented ontology of philosopher, ecologist and realist magician Timothy Morton to evolve their own theory of ‘slow thinking,’ at once an expressive mode and a philosophy of engagement. “In a very direct way, the basis of the idea is thinking at the speed of mineral exchange in a forest, or the movement of tectonic plates to make mountain ranges,” explains Twidale. “Something less human, less capitalist, less instant,” adds Avramovic. “In some way it’s banging up against this idea of accelerationism, trying to think of some sort of alternative where instead of pushing to extremes, maybe you need to slow down and be able to think in the same key as the world around you,” continues Twidale. “That could be the natural world, or the inorganic world, or it could just be your neighbors.”

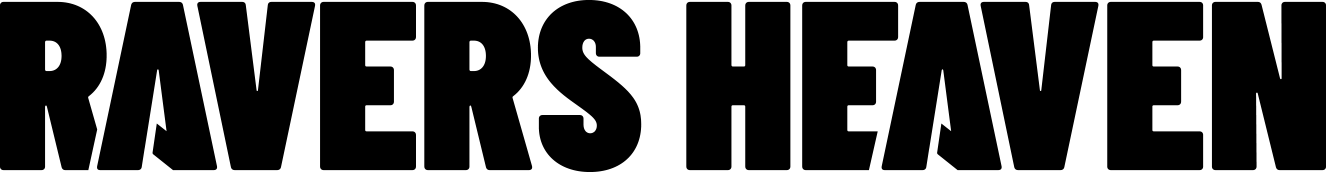

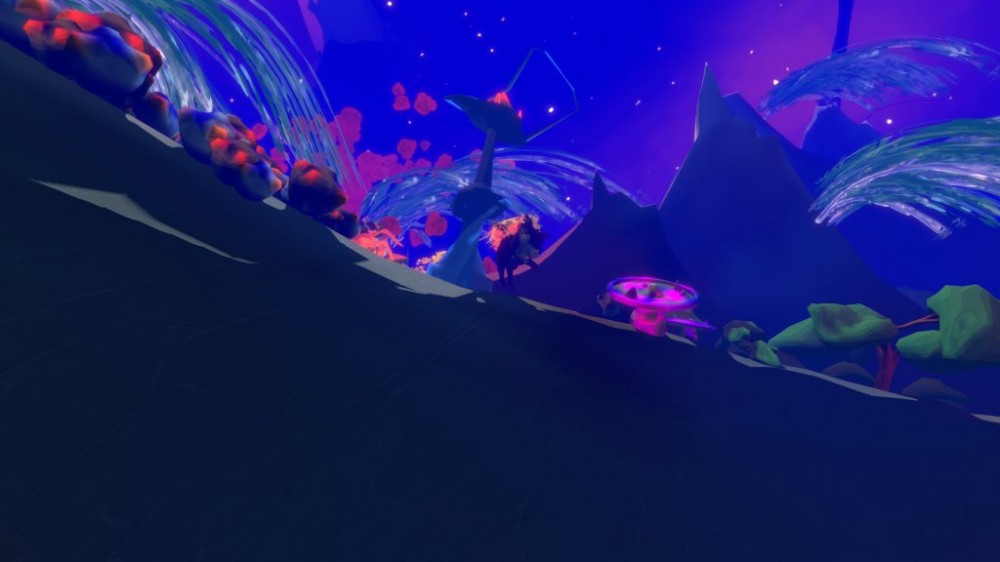

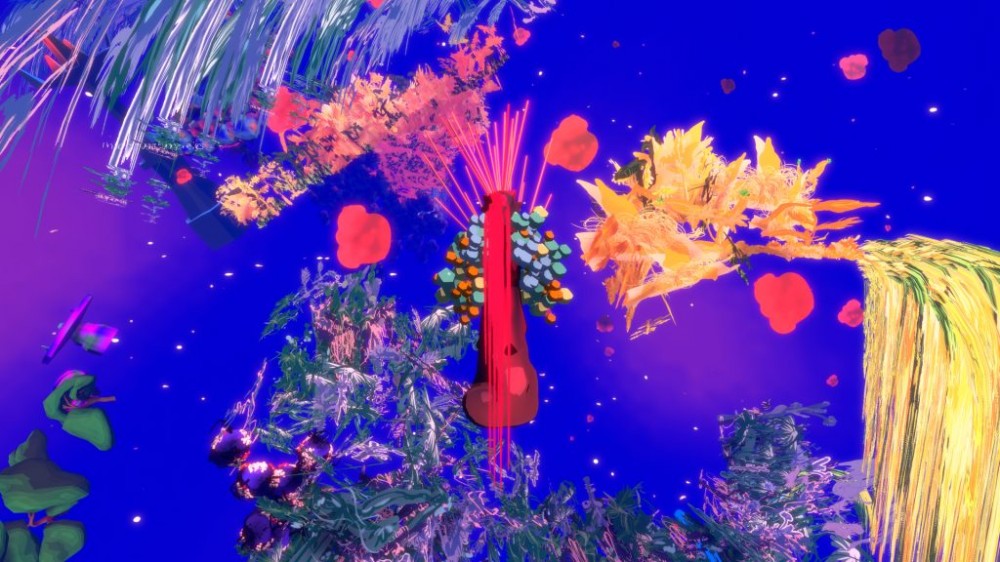

In Supreme, Xenoangel collapse these definitions into a self-contained, symbiotic ecosystem, following the progress of a monolithic world beast and the organisms that have taken up residence on its gargantuan back. “There is this myth, which is present in many cultures, of a world existing on the back of a creature, so we created a completely imaginary beast,” says Avramovic. Created using a synthesis of 3D animation, A.I. systems adapted from video game code, collaboratively sourced text and a painterly approach to color and composition, the world beast is presented to us in a fluid succession of view points, ranging from the smallest, granular scale, where the observer glimpses the world from the perspective of its most minute texture, to a roving, planetary scale view, where we are able to observe the world beast in its enormous totality. Teeming with technicolor life, radioactive foliage and jutting rock formations house incomprehensible lifeforms, lumpen, tendrilled and curious. Throughout the course of the work these lifeforms explore and adapt to their surroundings, seeking to synchronize with the world beast by excavating artefacts from the world beast’s past, embedded within its huge form and in so doing harmonizing with the world beast’s song, finding a means of expressing their interdependency through resonance. “The name ‘Supreme’ comes from this supreme type of relation,” explains Avramovic, “where the inhabitants on the back of the beast are synchronized with the beast. The creatures of Supreme are trying to synchronize with the beast, with the world, and they do it through their singing. They’re listening to the sounds of the beast and they are making their sounds in harmony. The more synchronized they are, the more artifacts they will be able to find and rediscover messages from the previous world.”

Each of these artifacts is represented by a virtual object, objects which appeared in a previous Xenoangel work, The Zone, an act of artistic cannibalisation which in itself embodies interconnected and symbiotic aesthetic relations. Each artifact also corresponds to a different text, contributed by six collaborators tasked by Xenoangel to write a response to the work and the broader themes of symbiosis and interdependence. Manifesting different perspectives of the same ecosystem and organism, Serafín Álvarez (in collaboration with the neural net-enabled A.I. language model GPT-3), Paul Robertson, Roc Jiménez de Cisneros, Phoebe Wagner, Corinna Dean of The Archive for Rural Contemporary Architecture and the experimental performance collective VVAA all put forward variations on Timothy Morton’s conception of the symbiotic real, a term that implies non-hierarchical solidarity between human and non-human entities, describing the inseparability and inherent participation of organisms within a given ecosystem – a relationship manifested in the hybrid, symbiotic form of the world beast. In the online iteration presented above a poem written in response to these texts by Xenoangel serves as both lore and language for the world beast and its inhabitants, an adapted corpus of free association and expression that works to capture the atmosphere of the world beast, rather than attempt to explain its symbiotic existence. Thus the world beast’s inhabitants are recorded as: “A people. / There are characters. Many. / And they are nodes. They are synapses,” while “Logging trucks form psycho-commercial traffic jams,” evoke some distant memory of “Mechanical ant lines with their sylvan swag.” Just as the creatures of the world beast enact an evolving practice of virtual excavation, Xenoangel inscribe a figurative excavation of myth, simulating a linguistic mode of mythic archaeology that functions with and through Supreme’s live simulation of the world beast.

“The critters are uncovering little snippets of a past world, or a world from a different timeline, understanding all these stories around their main story, like us discovering artifacts from the archaic people of our world,” explains Twidale. “There’s this really interesting idea from Federico Campagna, who talks about an end of a world, but not the end of all worlds. There is a world which follows and you need to imagine the entities which take it on. He says we can imagine them because the first people in the world are the archaic people of the world, so we imagined that these critters on the back of the beast are these archaic characters who arrive somehow and are trying to understand what their world is.” In this way, the role of Xenoangel’s discursive art practice is coded as the exploratory behaviour of the world beast’s inhabitants, a relationship delineated in the poem’s opening lines: “I’m thinking about something. / Slow Thinking is a myth.” By positing slow thinking as part of the fabric of the world beast’s mythos, the programmed excavation of the world beast’s history and the supreme, symbiotic relationship it has with its inhabitants doubles as the artists’ interrogation of their own thought. Their living, breathing world, “the shape shifting critter that took forever to shift shape,” becomes both vessel and avatar for this mode of thinking, one of Morton’s hyperobjects, objects so vast in temporal and spatial scope they become unplaceable, animated as both biome and beast. To look at it another way, slow thinking might be understood as one possible way of engaging with the enormity of Morton’s ecological thought, an engagement that serves as the lifeblood of both the world beast and of Supreme.

“Ecology has now become a very interesting topic for artists,” says Twidale. “Everything you’re trying to look at within ecology has parallels within society as well. Being able to think about the symbiotic real is to realize that you already live in this kind of interdependent, interconnected system, you can’t escape it. You have to learn how to maximize that and get the best out of it, you have to understand that you’re with this environment around you.” This grasp of their inherent interdependency is borne out not only in the duo’s artistic response, but also in Xenoangel’s approach to collaboration. “Our practice is becoming more and more collective in terms of involving more and more people,” continues Avramovic. “It’s such a nice ground to have a dialogue about these things. This sort of art is a good place to have paradoxical situations, because art allows that.” Ultimately, the paradoxical, impossible scope of slow thinking finds immediate expression in the languid progress of the world beast, its real time animation outlining Supreme as a marker by which to navigate Xenoangel’s broader philosophical investigations. By thinking slowly through the symbiotic real of this virtual ecology, the artists construct a contemporary myth as sense-making apparatus, an interdependent parable for navigating the present. “If you take the ecological viewpoint of those things, art has forever had a connection with nature,” concludes Twidale. “It’s not surprising that now people are interested in this approach, it’s just the way you look at nature and your position within it.”

For more information about Xenoangel and their work, you can visit their website and follow them on Instagram.